Vitiligo is a skin condition characterized by patches of skin losing their pigmentation, due to the destruction of the pigment producing melanocytes. This disease affects an estimated 1-3% of the world’s population, and has a strong familial association. Half the patients first recognize Vitiligo before 20 years of age, when it often appears in an area of minor injury or sunburn.

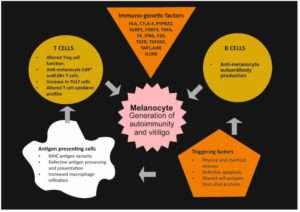

The central process in Vitiligo is the destruction of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. Fully blossomed lesions are totally devoid of melanocytes. Rarely, a superficial perivascular lichenoid mononuclear infiltration may be observed at the border of the depigmented areas. The exact cause of Vitiligo is unknown. Autoimmune mechanisms with an underlying genetic predisposition are the most likely cause. Antibodies to the melanocytes have been detected by immunoprecipitation in the sera of the patients with Vitiligo. Also, sera from patients with Vitiligo causes damage to melanocytes in cell culture, suggesting that the antibodies present in sera of affected patients are involved in the pathogenesis of Vitiligo.

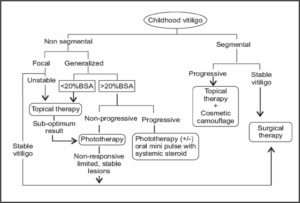

Childhood Vitiligo

Childhood Vitiligo differs from adult-onset Vitiligo for several features including increased incidence of the segmental variant, higher prevalence of halo nevi, and more common family history for autoimmune diseases and atopic diathesis. Trigeminal area is the most common site involved. Half the cases are associated with white hair (poliosis).

Types of Vitiligo

The most characteristic types include generalized vitiligo, focal vitiligo, acral vitiligo, acrofacial vitiligo, segmental vitiligo and vitiligo universalis. The segmental type of vitiligo is more often seen in children, as it starts generally earlier in life than the non-segmental one.

Associated Comorbidities in Childhood Vitiligo

Other cutaneous abnormalities include leukotrichia, premature gray hair, halo naevi and alopecia areata. Iris and retinal pigmentary abnormalities and deafness may be present. Systemic diseases associated include thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, Addison’s disease and multiple endocrinopathy syndrome. Presence of leukotrichia, associated with autoimmune disorders and family history are poor prognostic factors. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is 2.5 times more frequent among children and adolescents with Vitiligo than in a healthy age and sex-matched population. It usually follows the onset of Vitiligo. A family history of vitiligo is associated with earlier age of onset, among pediatric patients, those with a positive family history are more likely to develop Vitiligo before 7 years of age.

The major differential diagnoses are the post inflammatory hypomelanoses for nonsegmental Vitiligo and nevus depigmentosus for segmental Vitiligo.

Pathogenesis of Vitiligo

Clinical features of Vitiligo

The most common presentation of Vitiligo is totally amelenotic (i.e. milk or chalk white) macules or patches surrounded by normal skin. The lesions characteristically have discrete margins, and they can be round, oval, irregular or linear in shape. The borders are usually convex, if the depigmenting process was ‘invading’ the surrounding normally pigmented skin. The lesions enlarge centrifugally over time, and the rate may be slow or rapid. Vitiligo macules and patches range from millimeters to centimeters in diameter and often vary in size within areas of involvement. The incidence of leukotrichia varies from 10% to more than 60%, as follicular elanocytes are often spared in vitiligo.

Any of the clinical variants of vitiligo may occur in childhood. Vitiligo vulgaris is the most common clinical type observed in various clinical studies, followed by focal vitiligo and segmental vitiligo. Acrofacial and mucosal vitiligo have a lower incidence in childhood. The rarest type seen during childhood is the universal vitiligo.

Common initial site of onset of both NSV and SV in children is the face and neck. In NSV, initial lesions are periocular, perinasal or perioral, and gradually spread to other body parts, in a more or less symmetrical manner. Perineum, perianal area and, in infancy, the diaper area may be the initial site of occurrence of skin lesions. Individual vitiligo macules may enlarge attaining a geographic pattern or there may be appearance of new lesions at other sites. Although extensive areas of depigmentation may be present, majority of the children have <20% body surface area (BSA) involvement. Focal vitiligo may subsequently evolve into generalized disease.

Koebner phenomenon may be noted in both SV and NSV in children, more commonly in the latter type. In SV, Koebnerization is confined only to the involved segment. Koebnerization may be more frequent in childhood vitiligo because of higher mobility and playfulness in this age group. Presence of Koebnerization is indicative of the disease activity.

Diagnosis of Vitiligo

Diagnosis of Vitiligo is mostly clinical. In children with fair skin, it may be difficult to differentiate a lesion of Vitiligo from the surrounding normal skin. In these cases, examination under Wood’s lamp is helpful. Complete blood count and fasting blood sugar should be performed as a routine work-up for all patients. In case of diagnostic difficulty, skin biopsy may be taken; histopathological examination shows total absence of melanocytes in established lesions of Vitiligo.

In early lesions, melanocytes are still retained but with multiple abnormalities like vacuolization, dilated endoplasmic reticulum and granular deposits. Presence of mild inflammatory infiltrate is sometimes seen, and is indicative of disease activity.

Associated autoimmune disorders should be ruled out in the pediatric age group. Screening for autoantibodies may be performed if facilities are available. Antinuclear antibody may be positive even in normal children. Thyroid function status of the child is assessed by estimating T3, T4 and TSH levels. Coexistence of autoimmune thyroiditis may be ruled out by the estimation of antithyroglobulin antibody (anti-Tg) and antithyroperoxidase antibody (anti-TPO).

Differential Diagnosis of Childhood Vitiligo

Vitiligo and Quality of Life in Children

Study shows that vitiligo is related to depressive symptoms in children. A similar effect was not detected in adolescents, even though Vitiligo has a disfiguring and stigmatizing nature, which could affect identity formation and self-definition.

Treatment of Childhood Vitiligo

Various therapeutic modalities are available for the treatment of Vitiligo. However, all of these cannot be used with respect to children. Medical therapy is considered as the first line of management in this age group. All children with widespread Vitiligo should undertake photoprotection preferably with opaque sunscreens during daytime outdoor activities. In general, localized Vitiligo is treated with topical therapy. Widespread or generalized disease is managed with phototherapy or systemic therapy. Surgical methods may be chosen for stable (size of the lesion is stationary for > 2 years and no new lesion has developed recently) localized Vitiligo and SV. Certain clinical features are poor prognostic markers for treatment. These include acral Vitiligo, presence of leukotrichia over vitiliginous area and lesions over bony prominences like elbow, knee and ankle.

Following table shows various therapy for Vitiligo

Medical Treatment

Topical Therapy

Mid-potent topical corticosteroids are the first-line therapy for children with localized Vitiligo. Although high-potency steroids are more effective in Vitiligo, these are not recommended for use in children. It requires long-term therapy for several months, increasing the chances of developing tachyphylaxis and local side effects like atrophy, telangiectasia, hypertrichosis and striae. There are risks of serious side effects like glaucoma (prolonged application on periorbital Vitiligo), suppression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and growth retardation (longterm use over large BSA). Hence, parents should be cautioned about the inadvertent use of topical steroids.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI), tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are effective alternatives to topical corticosteroids in terms of avoidance of side effects of the latter.

In an open comparative trial of mometasone cream (0.1%, once-daily application) and pimecrolimus cream (1%, twice-daily application) in the treatment of localized childhood Vitiligo, the repigmentation rates were 65% and 42%, respectively, at the end of 3 months. Mometasone cream was found to be equally effective in all body parts whereas pimecrolimus was effective only over the face.

TCIs are slower to exert beneficial effect compared to topical corticosteroid. Best response is observed on the thinnest areas of the skin (eyelids). As the skin barrier function is not compromised in children with vitiligo (unlike atopic dermatitis), highest strength (0.1%) of tacrolimus may be used safely. Calcineurin inhibitors are not yet approved for the treatment of Vitiligo and are not recommended for use in children <2 years.

Topical calcipotriol has been found to be effective in the treatment of Vitiligo in children and adolescents. In a trial of topical calcipotriol in childhood Vitiligo, repigmentation was recorded as early as 4 weeks of treatment. Combination therapy of topical corticosteroids and calcipotriol may be used to reduce the side effects of corticosteroids as well as to enhance the efficacy of calcipotriol as the latter may not be as effective when used as monotherapy. Side effects of calcineurin inhibitors and calcipotriol are mild and transient and

hence, easily tolerated by children. Recalcitrant cases of widespread Vitiligo or universal Vitiligo with only a few islands of normal skin may be considered for total depigmentation therapy with 20% monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (MBEH), with an advice of life-long stringent photoprotection.

Systemic Therapy

Rapidly progressive generalized Vitiligo in older children and adolescents may be treated with a short course of systemic steroid. A better way to avert the side effects is administering oral betamethasone as a single morning dose (0.1 mg/kg body weight) on two consecutive days in a week (oral mini-pulse therapy) for 12 weeks, and thereafter reducing the dosage by 1 mg/month for the next 3 months. Pasricha et al have studied the effect of oral mini-pulse therapy (OMP) in children and adults with extensive or fast-spreading Vitiligo, and have observed a 26-50% response in 25%, 51-75% response in 7.5% and >75% response in 15% of patients. Phototherapy may be added to such regimen. Majid et al have used methylprednisolone OMP in combination with topical fluticasone for 6 months in 400 children with progressive vitiligo. Complete halt of progression was noted in >90% of the children after initiation of therapy, and >65% of children had well to excellent repigmentation at the end of the study period.

Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy

Systemic photochemotherapy with psoralen-ultraviolet A (PUVA) is contraindicated in small children and can be used only beyond 12 years of age. It is used when >20-25% of the BSA is involved or in patients in whom other treatment modalities are not giving optimum result. Topical PUVA can be used even in younger children with limited BSA involvement. Various authors have reported an overall response rate of approximately 75% in 50-60% of the children with Vitiligo treated with topical or oral PUVA therapy.

Oral supplementation of L-phenylalanine (a precursor of tyrosine in melanin synthesis) and UVA phototherapy have been found to be effective in children with extensive Vitiligo (50-100% repigmentation in 69% of children).

Narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) phototherapy is an effective modality for the treatment of generalized childhood Vitiligo with >20% BSA involvement. There are several studies on the effectiveness of NB-UVB phototherapy in children. Brazzelli et al have reported this therapeutic modality as effective and safe in children. Best repigmentation occurred on skin lesions over the face and neck, and moderate response was seen in lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions over the acral region (fingers and toes), bony prominences and less-hairy areas (wrist, ankle and joints) were poorly repigmented. The side effects recorded were minimal erythema, amenable to emollients and topical steroid.

Excimer laser (308 nm)/targeted UVB phototherapy has been used in the treatment of localized childhood Vitiligo with the advantage of more focused therapy at the site of lesion, avoiding the risk of photoageing of the surrounding skin. Cho et al have treated 30 children with localized Vitiligo (40 patches) with 308 nm excimer laser. A repigmentation rate of >50-75% was recorded in this trial, especially over the face, neck and trunk. Side effects related to this mode of therapy are usually minimal and transient. Repigmentation following phototherapy is either marginal or perifollicular.

During phototherapy, genitalia of the children should always be protected. It is preferable to follow the “skin-saving principle,” i.e. shielding of uninvolved body sites during phototherapy. Already repigmented body parts should also be covered with clothing during further therapy. Carcinogenic potential of NB-UVB phototherapy in children is not yet determined. However, theoretically, there may be an increased chance of developing long-term skin cancers because of the higher number of expected years of life in children. Such risk may be lower in children with darker skin types. In resource-poor countries, the facility of phototherapy is available mostly in tertiary health care centers. Hence, it may not be easily accessible to families from remote localities. Moreover, multiple hospital visits confer loss of school days of children and working days of parents, reducing compliance to treatment.

Surgical Treatment

Only stable localized Vitiligo lesions (segmental or non-segmental), unresponsive to other treatment modalities, are chosen for surgical treatment. Surgical procedures are not performed in very young children. This is because segmental or stable focal lesions in younger children extend proportionate to their body growth. Moreover, success of many surgical procedures depends upon the postoperative immobility of the operated part, which becomes difficult to maintain in young children. Older children and adolescents may be counseled about the procedure and the possible outcome of the surgery to achieve their cooperation. The restrictive factors for surgical procedures are inability to treat larger area and the risk of Koebnerization of the donor site.

Among the various surgical techniques, suction blister epidermal grafting (SBEG) has been found to be most convenient and effective for children and adolescents. The success rate of this technique is better in children as compared to adults. However, this procedure requires prolonged immobility to facilitate smooth generation of the blisters, more so in children because of their strong dermoepidermal adherence. Hence, it may be a difficult task to keep children in restricted posture till the required duration. Surgical procedures in combination with medical therapy have been tried in childhood vitiligo. Non-cultured autologous epidermal transplantation has been used successfully in children and adolescents with stable vitiligo. Cultured melanocyte transplantation is a relatively tedious technique requiring specialized set up, trained staff and a preparation time of 6-8 weeks.

Cosmetic Camouflage

Good-quality cover-up cosmetics (Dermacolor) may be used to cover localized Vitiligo lesions over exposed body parts in children. Well-counseled older children may use this as an effective adjunctive while on treatment or when failed to respond to other treatment modalities.

What’s New in Vitiligo?

Latanoprost, commonly used in the treatment of ocular hypertension was tried in Vitiligo based on the presence of irreversible iris pigmentation and reversible periocular hyperpigmentation observed in these patients. PGF2α, however, exerts its effect indirectly through induction of COX-2 and PGE2 and has been reported to be a promising therapeutic option for Vitiligo in both animal and human studies with increased efficacy when combined with phototherapy. Other Treatment Methotrexate, known for its use in inflammatory and immunemediated conditions, such as psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease, has also been studied in treating Vitiligo. In childhood Vitiligo, it should be used with care.

Tofacitinib is a recently approved drug for rheumatoid arthritis and acts as a Jak inhibitor, disrupting specific inflammatory pathways that signal through proteins called Jaks, of which there are four – Jak1, Jak2, Jak3, and Tyk2. While only a single patient, this report is indeed very exciting, as it suggests that Jak inhibitors may provide a new effective treatment for Vitiligo. IFN-g signaling pathway (which requires Jak1 and Jak2) is critical for vitiligo progression and maintenance.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, significant progress has been made in understanding the complex and multifactorial pathogenesis of Vitiligo. It is now theorized that intrinsic metabolic, neuronal, and/or biochemical cutaneous perturbations trigger autoimmune melanocytic destruction, to which patients may be predisposed by certain genetic mutations and polymorphisms. How different pathogenic mechanisms give rise to Vitiligo subtypes remains to be further elucidated. There is no cure for vitiligo at present. However, a variety of advances in medical and surgical treatments as well as combinations of the two working synergistically have shown the ability to improve patients’ disease state and quality of life. A number of clinical trials are underway, and the future looks promising for patients afflicted with this traditionally stigmatizing and challenging condition.

World Vitiligo Theme 2017

Step up for Vitiligo: A Call for Truth, Hope and Change!