Introduction

Acne scarring presents a challenging aesthetic problem to the aesthetic practitioner. Acne is defined as a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous glands. It is experienced by 80% of individuals between the age group of 11-30 years. However the severity, age of onset and duration vary widely. [1]

Acne lesions can lead to scarring due to imbalance of matrix degradation and collagen biosynthesis during the process of wound healing. [3]

Aggressive treatment of acne at an early stage prevents scarring. But once acne scarring has occurred, the physician and the patient are left to struggle with the different available options for improving the appearance of the skin. [1]

Acne scars are categorized as:

- Hypertrophic

- Atrophic

Atrophic acne scars can be further classified as:

- Ice pick

- Rolling

- Boxcar

The boxcar type can be further divided into deep or shallow. As such there is some variation with all the types. This classification system is developed keeping in mind the practicality and therapeutic options available for treatment. [1, 3]

Hypertrophic acne scars are described as raised, erythematous and firm nodular lesions whose growth is limited to original tissue injury site.

Ice pick scars are deep, narrow (<2mm) and sharply marginated epithelial tracts extending vertically to the reticular dermis or up to the subcutaneous tissue. [1]

Rolling scars are wider usually 4-5 mm. They occur as a result of dermal tethering of otherwise normal appearing skin. [1]

Boxcar scars are sharply delineated epithelial tracts that extend into the dermis but, unlike ice pick scars do not taper at the base. [3]

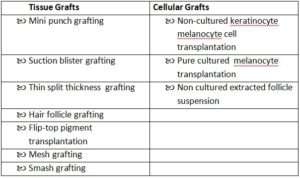

Histopathologically, acne scarring destroys the underlying collagen which makes it difficult to treat. Many treatments have been tried and tested in past with varying degrees of success. Some of which are dermabrasion, chemical peels, Subcision, punch excision followed by suturing or grafting, micro-needling and dermal fillers. [2, 3]

Nowadays with advancement in the laser technology and availability of new resurfacing lasers, it is becoming easy to treat this therapeutically difficult condition. [3] Lasers allow for direct smoothening, collagen neogenesis in the scarred skin and contraction of acne scars. These lasers far exceed the efficacy of traditional treatment.

History of Laser Resurfacing

Lasers were there in the market since long but the field was revolutionized by Anderson and Parrish in 1983 [4] when they elucidated the principles of selective photothermolysis. In order to achieve maximal target destruction and minimal damage to the surrounding tissues the wavelength of laser, pulse duration and fluence each must be carefully chosen. [3]

The Pulsed Dye Laser (PDL) was the first reported laser for scar improvement in the year 1993. [5] Following this and with the advancement in the laser technology the laser scar revision has tremendously progressed. Several qualities of scar influence the choice of laser wavelength and treatment parameters including the size, colour and texture of scar. [3]

Lasers in Hypertrophic Acne Scars

PDL was the first Non Ablative Laser system being successful in the treatment of hypertrophic, erythematous facial acne scars.

PDL acts by:

- Reducing transforming growth factor –β expression

- Deposition of type 3 collagen

- Proliferation of fibroblasts

- Thermal Coagulation of collagen fibres

- Breaking of disulphide bonds followed by Neocollagenesis. [3]

In a study, 10 subjects having shallow to moderately deep facial acne scars, who underwent a single treatment session of 585nm PDL. All 10 subjects showed marked clinical improvement and no adverse effects were reported. [6]

Post treatment purpura which persists for a few days is the commonest side effect following treatment with PDL. Edema which occurs at the treatment site usually subsides within 48 hours. In order to protect the skin, for the first few post-operative days a topical healing ointment can be applied. There should be strict sun avoidance and sunscreens should be used. Patients should be advised to clean the treated areas gently with water and soap on daily basis. [3]

Hence 585nm PDL is the laser of choice in the treatment of hypertrophic erythematous acne scars.

Lasers in Atrophic Acne Scars

Atrophic acne scarring treatment with lasers is a precise and well-tolerated procedure. It shows clinically demonstrable efficacy with minimum side effects. It can also be used in conjunction with other scar treatments.

Ablative Resurfacing:

Two wavelengths for ablative laser resurfacing are:

- Infrared CO2 (10,600 nm)

- Er:YAG (2940nm)

Target chromophore for both these lasers is water. Hence intracellular tissue water absorbs the emitted energy which leads to heating and vaporization of the superficial skin. [3]

These lasers work by causing shrinkage of collagen, neocollagenesis and collagen remodelling which leads to marked improvement in acne scarring. [3]

The prolonged histological and clinical effects of high energy pulsed CO2 laser was documented in 1999. In this prospective study which included 60 patients, continued clinical as well as histological improvement showing dermal remodelling and progressive neocollagenesis was noted for 18 months after resurfacing with CO2 laser. [7]

When the Er: YAG (2940nm) laser is compared with the CO2 (10,600nm) laser, one can observe that 2940nm wavelength is more efficiently absorbed by water. Er: YAG has much shorter pulse duration than the CO2 laser. But since Er: YAG causes limited thermal injury to the skin compared to that of CO2 the amount of collagen contraction is also less. [3]

To overcome these limitations, modulated Er: YAG and combination Er: YAG-CO2 lasers were developed. These lasers emit combination of short ablative pulses as well as long coagulative pulses. The result was improved haemostasis and increased collagen shrinkage and remodelling. The modulated Er: YAG was thus similar in efficacy to that of CO2 lasers. [3]

In a study that assessed the outcome of different Er: YAG lasers in different types of acne scarring in 158 patients, showed improvement in ice pick and boxcar (shallow) scars. Long pulse Er: YAG laser showed improvement in rolling and boxcar (deep) scars. [8]

Though Ablative Laser Resurfacing for acne scars is an OPD procedure careful history taking, consent, clinical photographs, preoperative counseling particularly regarding the post procedure recovery period is required. [3]

Absolute contraindications:

- Active viral, fungal or bacterial infection

- Inflammatory skin condition (e.g. Psoriasis, eczema, etc.)

- History of keloids

- Use of oral retinoids within the preceding 6-month period

Potential complications post laser scar resurfacing includes dermatitis or infection, which usually occurs during the 7-10 days re-epithelialization process. Prophylactic antibiotics/antibacterial reduces the risk of infection. [9-11]

When aggressive laser parameters are used, it may lead to complications such as ectropion and hypertrophic scarring. [3]

Non Ablative Resurfacing

Most widely used non-ablative systems are:

- 1320 nm Nd: YAG

- 1450 nm Diode

- 1064 nm Nd: YAG

These lasers deliver deeply penetrating infrared wavelengths with simultaneous epidermal cooling. This leads to neocollagenesis through dermal heating while maintaining the integrity of the epidermis. [12]

The 1320nm Nd: YAG laser has shown significant improvement in atrophic acne scars reported by both the patients and physician without evidence of notable adverse effects. [3]

The 1450nm diode laser showed modest improvement in atrophic acne scarring after 4-6 sessions. [3] In a spilt face study that compared the effects of 1450nm

diode with 1320nm Nd: YAG, after 3 monthly sessions, both lasers demonstrated a mild improvement, but there was greater clinical effect with the 1450nm diode laser. There were no adverse textural changes with both the lasers. [3]

Atrophic acne scarring treated with 1064nm Nd: YAG showed mild to moderate improvement, which was confirmed histologically. [3]

Though the results achieved by non-ablative laser systems are inferior in comparison to ablative one, the low adverse profile of these lasers compensate for their reduced clinical efficacy.

Fractional Laser Resurfacing

Fractional Lasers can be of two types:

- Non Ablative Fractional Lasers (NAFL)

- Ablative Fractional Lasers (AFL)

Fractional lasers work by creating Microscopic Thermal Zones (MTZ). MTZ are microscopic non-contiguous columns of thermal energy in the dermis. The tissue surrounding each MTZ remains intact which results to quick healing. [3]

There is also improvement in superficial dyspigmentation because NAFL causes gradual exfoliation of the epidermis. This is an added advantage of NAFL over ablative lasers. NAFL requires a series of treatment to achieve optimum clinical improvement. [3]

Many studies have shown clinical improvement of at least 50% or more in atrophic acne scarring after a series of three consecutive sessions. [3]

The consensus guidelines for NAFL for atrophic acne scarring for different types of skin are: [3]

Fitzpatrick skin types I–III

- Energy – 30-70mJ

- Level of treatment – 7–11

- Number of passes – 8-12

Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI

- Energy – 30–70 mJ

- Level of treatment – Low treatment density to avoid Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation

- Number of passes – are also a few

Ablative Fractional Lasers, in addition to creating MTZ, vaporize the Stratum Corneum. [3] So the post procedure appearance is similar to that of an ablative laser. There have been numerous studies regarding the success of AFL in treating atrophic acne scars. [3]

The ideal patients for fractional laser resurfacing are patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, and III but Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI patients can also be treated. [3]

While treating patients with AFL, adequate patient education and preoperative assessment are necessary in order to avoid pitfalls and maximize patient outcomes. With fractional laser technology, the chances of pigmentary alteration and unexpected scarring are much less when compared with that of fully ablative lasers. [3]

The energy settings will differ depending on what type of laser is used and also on the severity and type of acne scars. Improved clinical efficacy is noted with higher energy settings, but there are also chances of increased adverse events such as: [3]

- Pain

- Erythema

- Postoperative dyspigmentation

Patients undergoing NAFL are advised to use a mild cleanser as well as a moisturizer several times in a day following each treatment session for the first few days. Sun exposure should be avoided during this period. To prevent infection and other complications in patients undergoing AFL, open or closed wound dressing is advised for the first few post treatment days. [3]

Complications associated with fractional laser resurfacing: [3]

- Erythema

- Periocular edema

- Xerosis

- Slight darkening of the skin

- Acneiform and herpetic eruptions

- Post inflammatory hyperpigmentation

Conclusion:

Acne scarring is a common problem and patients mostly resort to treatment for cosmetic improvement. Most of the treatments that were available in the market were inadequate or insufficient in treating acne scarring. In order to overcome this, Laser therapy for scar revision was investigated.

Different types of acne scars are treated effectively nowadays with different types of lasers. 585 nm Pulse Dye Laser is quite effective for hypertrophic acne scarring. Depending on the individual patient circumstances atrophic acne scarring can be treated successfully with Ablative lasers and Fractional Ablative and Non-Ablative laser systems. These lasers work by contouring the scar tissue via collagen contraction and neocollagenesis. The best outcome for laser scar revision is when the characteristics of scars are evaluated thoroughly the treatment is individualized for each patient. And most importantly both the physician and patient have realistic expectations and treatment goals.

References:

- Jacob C, Dover J and Kaminer M. “Acne scarring: A classification system and review of treatment options”. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology (2001); 45: 109-117.

- Jordan R, Cummins C and Burls A. “Laser resurfacing of the skin for the improvement of facial acne scarring: a systemic review of the evidence.” British Journal of Dermatology (2000); 142: 413-423.

- Sobanko J and Alster T. “Management of Acne Scarring, Part I.”American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (2012); 13: 319-327.

- Anderson RR and Parrish JA. “Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation.”Science(1983); 22: 524-7

- Alster TS, Kurban AK and Grove GL, et al. “Alteration of argon laser induced scars by the pulsed dye laser.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine(1993); 13: 368-73

- Patel N and Clement M. “Selective Nonablative Treatment of Acne Scarring With 585 nm Flashlamp Pulsed Dye Laser.”American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (2002); 28: 942-945.

- Walia S and Alster T. “Prolonged Clinical and Histologic Effects from CO2 Laser Resurfacing of Atrophic Acne Scars.”American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (1999); 25: 926-930.

- Woo SH, Park JH and Kye YC. “Resurfacing of different types of facial acne scar with short-pulsed, variable-pulsed, and dual-mode Er:YAG laser.”Dermatologic Surgery(2004); 30: 488-93

- Walia S and Alster TS. “Cutaneous CO2 laser resurfacing infection rate with and without prophylactic antibiotics.”Dermatologic Surgery(1999); 25: 857-61

- Alster TS and Nanni CA. “Famciclovir prophylaxis of herpes simplex virus reactivation after cutaneous laser resurfacing.” Dermatologic Surgery(1997); 25: 242-6

- Beeson WH and Rachel JD. “Valacyclovir prophylaxis for herpes simplex virus infection or infection recurrence following laser skin resurfacing”. Dermatologic Surgery(2002); 28: 331-6

- Friedman PM, Skover GR, Payonik G, et al. “3D in-vivo optical skin imaging for topographical quantitative assessment of non-ablative laser technology”. Dermatologic Surgery(2002); 28: 199-204.