The lack of awareness of PCOS among patients and health care professionals made 70% of women with PCOS remain undiagnosed- Australian study1

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinological abnormality in patients with acne with an incidence of 5–10%, Around 30% of all patients with PCOS show clinical features of acne together with clinical or laboratory aspects of hyperandrogenism, oligo-amenorrhoea and ovarian cysts.2 Studies of PCOS in India carried out in convenience samples reported a prevalence of 3.7% to 22.5%, with 9.13% to 36% prevalence in adolescents only.

There is a high incidence of psychological issues amongst women with PCOS such as depression, anxiety and eating disorders when compared to the general population. A woman with PCOS may need to see a general practitioner, dietician, dermatologist, psychologist, exercise physiologist, endocrinologist, gynaecologist and infertility specialist.

Pathophysiology of acne and hyperandrogenism in PCOS

Before puberty, the adrenal glands produce increasing amounts of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), which can be metabolized into more potent androgens in the skin, driving enlargement of the sebaceous gland and increased sebum production; this is a prerequisite for acne in all populations.

Molecular aspects

Sebocytes and keratinocytes of the pilosebaceous follicle infundibulum in patients with acne have androgen receptors that are both more numerous and more sensitive than those in normal subjects.3,4 The androgenic activity may be induced by potent androgens, such as testosterone and dehydrotestosterone (DHT) and weak androgens, such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, which reach the skin through the bloodstream or can be produced locally on the skin. In sebocytes and keratinocytes of the infundibulum the enzyme 5-alpha reductase type 1 can transform testosterone into DHT and this enzyme activity is greater in the follicular infra-infundibulum than in the epidermis. DHT acts 5–10 times more strongly than its precursor testosterone.

Clinical aspects

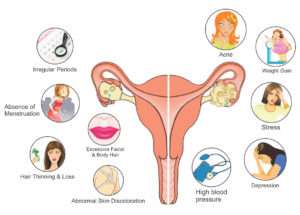

PCOS patients can present with any one or in combinations with various clinical features such as hirsutism, female-pattern androgenetic alopecia, irregular menstrual periods, obesity, deepening of the voice and clitoridomegaly. Infertility, diabetes, insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease can also be associated with PCOS.

Androgen excess is often characterized by nodulocystic acne, dispersed rapidly growing comedones and severe, sudden-onset acne. It is wise to remember that many women with androgen excess can still have a normal menstrual period.5, 6

Diagnosis

The Rotterdam 2004 Consensus Workshop (Revised 2003) recommended that two of the following criteria should be present to establish the diagnosis of PCOS:

1) Chronic oligo or anovulation for more than 6 months

2) Clinical and/or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, and

3) Polycystic ovaries in ultrasound.

Other disorders that mimic PCOS phenotype should be excluded such as thyroid dysfunction, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinaemia, androgen-secreting tumours and Cushing’s syndrome.

Androgen assessment in women generally remains controversial. Calculated bioavailable testosterone and calculated free testosterone can be used interchangeably as a marker of testosterone. The FAI (100 x (total testosterone/SHBG)) is also a widely used measure of androgens. Calculated bioavailable testosterone, calculated free testosterone or free androgen index should be first line investigation; androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate could be used as second line investigation for biochemical determination of hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome.

Levels of androgens outside the expected range can also be indicative of other diseases like, high levels of testosterone (> 150– 200 ng/dL), in particular if associated with normal levels of DHEA, are suggestive for ovarian tumour, high levels of DHEA (> 8000 ng/mL) are suggestive for adrenal tumours. Slightly elevated levels of DHEA (4000–8000 ng/mL) are found in CAH, PCOS and Cushing disease. A ratio of LH/FSH greater than 2: 1 is indicative of a possible androgenism such as in PCOS.

Blood levels of Prolectin largely above the normal values may be related to a prolactinoma and a head scan, preferably a MRI, should be performed. High levels of 17-OHP and a positive adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test are essential to make the diagnosis of CAH. The best time to run laboratory tests is within the first week of the menstrual period.

If biochemical hyperandrogenism is needed for the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome, the oral contraceptive pill could be withdrawn for three months to facilitate appropriate hormonal assessments. However, the risk of unplanned pregnancy needs to considered and weighed up against potential benefits of early diagnosis. Contraception may still need to be otherwise managed during this time.

Given the apparent lack of specificity of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound in adolescents, generally, ultrasound should not be recommended first line and if pelvic ultrasounds are to be ordered in adolescents, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Testing of fasting insulin and lipids should be requested in patients with PCOS due to the metabolic consequences that occur more frequently in these cases.

Insulin levels should be measured in overweight and obese patients and those with a family history of diabetes and not responding to treatment.

Those women with polycystic ovary syndrome should be considered at increased relative risk of Dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease (obesity, cigarette smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, lack of physical activity). To assess for risk of type 2 diabetes, in PCOS patients, age, gender, parental history of diabetes, hypertension, waist circumference, high GTT should be assessed.

Treatment

Hormonal treatment is indicated as first line of treatment in cases of papulopustular, nodular and conglobate acne in females with identified hyperandrogenism, in adult women who have monthly flare-ups and when standard therapeutic options are unsuccessful or inappropriate.PCOS. In comedonal and mild-to moderate papulopustular acne hormonal treatment is not recommended. It can take 3–6 months to see clinical improvement, although effects may be seen after one menstrual cycle.

Hormonal therapy

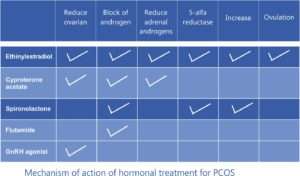

Hormonal therapies that can be considered for patients with acne include: COCs; anti-androgens like Cyproterone acetate (CPA), spironolactone, flutamide; and GnRH agonists. Metformin is not strictly classified as a hormonal therapy for acne, but it may be of help in some cases of hyperandrogenism with hyperinsulinaemia whether or not the patient is overweight.

COCs- The most commonly used oestrogen is ethinylestradiol (EE) and group of progestins includes CPA, chlormadinone and drospirenone, and derivatives of 19-nortestosterone (estranges and gonanes) like norethindrone, levonorgestrel, norgestrel, desogestrel, norgestimate and gestodene.7-10

Guidelines:

The derivatives of 19-nortestosterone interact with progesterone receptors and also cross react with androgen receptors, resulting in an androgen-like effect with possible worsening of acne.

COCs containing chlormadinone acetate or CPA performed better than levonorgestrel, CPA showed better acne outcomes than desogestrel; levonorgestrel performed slightly better than desogestrel; and a drospirenone-containing COC showed more effectiveness than norgestimate or nomegestrol acetate but less effectiveness than CPA in acne outcomes.

Several safety issues are related specifically to the use of oestrogens in COCs: breast tenderness, headache, nausea, bloating, hypercoagulability, increased cardiovascular disease, increased risk of endometrial and breast cancers. The use of COCs comes with several safety considerations. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and arterial thromboembolism are the most serious potential side-effects associated with COCs. Recent formulations of COCs with low dosages of EE (20–35 lg and 15 lg in some cases) reduce the risk of oestrogen-related side-effects.

CPA is a progestin that is used in combination with an oestrogen in the majority of the cases (such as in COCs) but sometimes it is prescribed alone. When used alone, at the recommended dose of 50–100 mg daily, CPA treatment may be initiated from the first or fifth day of the menstrual period and stopped on the 14th day just before ovulation. Side-effects are menstrual irregularities (amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea), breakthrough bleeding, breast tenderness, headache and nausea, although they tend to regress with time.

Spironolactone is a synthetic steroidal derivative of aldosterone that works as an aldosterone antagonist. Standard doses are 50–100 mg once or twice daily, taken with meals, with a steady-state daily dose range between 25 and 50 mg. Side-effects including menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness or enlargement are more common at higher doses, but usually they are mild in severity and a reduction of the dosage is sufficient to reduce them to acceptable levels. Spironolactone is contraindicated in pregnancy (FDA pregnancy category C) because of a potential for feminization of the male foetus and the use in combination with a contraceptive pill is advisable and recommended. The dose is titrated from 25 mg, with an increase of 25 mg every 20 days until the maximum dose of 100 mg has been reached, according to tolerability and blood levels of potassium.

Anti-androgen activity of Flutamide is mostly related to the inhibition of androgen receptors, in particular the ones that bind DHT. Flutamide can cross the placental barrier and cause a pseudohermaphrodite condition in a male fetus; it cannot be given to pregnant women. The standard dose used in acne ranges between 625 and 500 mg daily, which can result in an 80% improvement of acne.

Metformin causes decrease in insulin (about 20-30%) and testosterone (about 20%) with increase in SHBG. Metformin should not be kept as first line of treatment in adolescent and unmarried females with regular menses and devoid of anovulatory cycles. Metformin could be used alone to improve ovulation rate and pregnancy rate in women with polycystic ovary syndrome who are anovulatory, have a body mass index ≤30kg/m2 and are infertile with no other infertility factors. For treatment of infertility a referral to gynaecology should be made for ovulation induction.

Weight loss should be targeted in all women with polycystic ovary syndrome and body mass index ≥25kg/m2 (overweight) through reducing dietary energy (caloric) intake in the setting of healthy food choices, irrespective of diet composition. Exercise participation of at least 150 minutes per week should be recommended to all women with polycystic ovary syndrome, especially those with a body mass index ≥25kg/m2 (overweight), given the metabolic risks of polycystic ovary syndrome and the long term metabolic benefits of exercise. Of this, 90 minutes per week should be aerobic activity at moderate to high intensity (60% – 90% of maximum heart rate) to optimise clinical outcomes.

Mechanism of action of hormonal treatment for PCOS

References

- March, W., et al., The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Human Reproduction, 2010. 25(2): p. 544-51.

- Bettoli et al., Is hormonal treatment still an option in acne today. BJD, 2015: p. 37-46.

- Lai JJ,Chang P, Lai KP et al. The role of androgen and androgen receptor in the skin-related disorders. Arch Dermatol Res 2012; 304:499–

- Chen W,Thiboutot D, Zouboulis CC. Cutaneous androgen metabolism: basic research and clinical prospectives. J Invest Dermatol 2002; 119:992–

- Darley CR,Moore JW, Besser GM et al. Androgen status in women with late onset or persistent acne vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol 1984; 9:28–

- Thiboutot D.Acne: hormonal concepts and therapy. Clin Dermatol 2004; 22:419–

- Thiboutot D,Archer DF, Lemay A et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg of levonorgestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril 2001; 76:461–8..

- Leyden J,Shalita A, Hordinsky M et al. Efficacy of a low-dose oral contraceptive containing 20 μg of ethinylestradiol and 100 μg of levonorgestrel for the treatment of moderate acne: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:399–409.

- Maloney JM,Arbit DI, Flack M et al. Use of a low-dose oral contraceptive containing norethindrone acetate and ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of moderate acne vulgaris. Clin J Women’s Health 2001; 1:123–

- Lucky AW,Henderson TA, Olson WH et al. Effectiveness of norgestimate and ethinylestradiol in treating moderate acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997; 37:746–54.